February 2018

AN INTERVIEW WITH CHRIS YOUNG.

PDAN Admins interviewed Chris Young, an author, ex-social worker who has a diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder, and an individual who actively campaigns to lessen the stigma associated with BPD – amongst other things!

On April the 6th 2011, following his diagnosis of BPD, Chris set off northwards from his home in Edinburgh to walk around the edge of the UK to change the way people think about mental health. Armed with a rucksack full of ‘what if’, 11 packets of super noodles and a belief that people would be fabulous, Chris has relied solely on the hospitality of strangers.

In this interview Chris talks about some of the struggles he has faced throughout his life and how he has overcome them. Please remember this is Chris’ viewpoint, so you may have different views on some of the things discussed in this interview. That’s okay and we encourage that; please be respectful of other people’s viewpoints. We hope you enjoy reading it!

PDAN: Do you have any advice for people newly diagnosed with BPD, and for people who’ve struggled all their lives and still not got proper help?

Chris Young: Read something about BPD that doesn’t judge you or discriminate against you – ‘Walk a Mile’ (obviously!) or ‘The Borderline Personality Disorder survival guide’. Get the people around you (friends/ family/ loved ones/ professionals) to read the same stuff.

Find a peer support group. I found this incredibly validating – realising that people with the same condition as you have so many similar experiences to you.

Don’t buy into the ‘What’s wrong with you?’ rhetoric – think more in terms of ‘What happened to you?

Diagnosing BPD is often as much an art as a science. It’s very nuanced. Bear in mind in the U.K. there’s a move to call it ‘Emotionally Unstable Personality Disorder’ this is in part (I believe) an attempt to reduce the stigma attached to the condition. It’s very easy to get tied up with definitions – not least because we know the stigma attached to it by some (I repeat SOME) professionals – if you feel the label fits, work with it – don’t waste valuable energy on what is often a meaningless battle.

If you feel the label is wrong – get as much help as you can from those around you – collect evidence – get a second opinion from a psychiatrist. Make sure in your own mind that you’re not challenging it because you’d rather not have it, or because you’re afraid of judgement.

And that’s hard. Accept your symptoms as symptoms. It’s very easy to judge yourself & buy into the ‘pull yourself together’, ‘manipulative’ rhetoric around you.

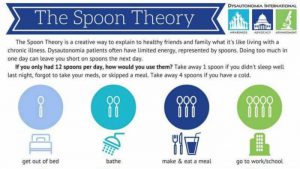

Your symptoms are manageable. I found ‘spoon theory’ really useful in not judging myself – take a look – to this day I talk about running out of spoons; see https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spoon_theory.

There are a number of treatments for BPD:

- Psychotherapy (group or individual) I had 2 years of open ended (this is key – it removes the stress of feeling out of control of our treatment) group psychotherapy

- Mentalization

- Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (I’m wary of this – friends of mine have been on the course and have found it a bit judgemental – that said, others have found it great)

- STEPP programme (I don’t know enough about this to really comment).

It really is horses for courses here. There are a bazillion (give or take) medications that can alleviate some of the symptoms of BPD. You should work closely with your psychiatrist/ possibly GP to work out which medication works best for you. A therapeutic dose of a suitable medication can help soften the hard edges you may experience in therapy. It’s important to experience therapy as much as you can – too many meds may prevent you from interacting with therapy in a useful way.

Your health authority may offer nothing – or something inappropriate – 8 weeks of cognitive behavioural therapy, for example, can do more harm than good. If this is the case – complain using the procedures the NHS has in place. Get as much support with this as possible too. There are usually a number of stages in this process – some health professionals may not fall over themselves to help you through the process. It’s important you’re supported by someone independent (usually citizens advice as a start point).

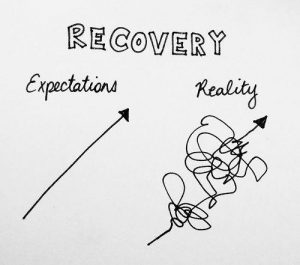

There’s a lot of talk in mental health circles about ‘Recovery’. Many mistakenly equate ‘recovery’ with ‘cure’. Don’t be one of them. I don’t think the term ‘recovery’ is very useful – especially since it’s been hijacked by the department of work and pensions and other agencies to mean ‘cure’ which can often limit your entitlement to the welfare benefits you’re entitled to.

On that subject, if you need to give up work, get all the help you can to apply for (and this depends on local policies). Universal Credit (this is a combination of a number of earlier benefits – it’s punitive and in no way ideal). That’s why it’s essential you get someone to help you through it – citizens advice, a social worker, there may be local agencies set up to help.

Employment and Support Allowance (ESA) this is a benefit for folk with long term health problems – BPD fits that description in areas that haven’t moved on to Universal Credit yet. Housing Benefit/ council tax benefit – provided by your local authority/ council – it does exactly what it says on the tin. Personal independence Payment (PiP) this is a benefit that has replaced disability living allowance – it has a personal care and a mobility component. Bo th Universal Credit and PiP claim forms are very much focused on physical disability – that’s why it’s ESSENTIAL to get help from someone who knows the system to complete them.

th Universal Credit and PiP claim forms are very much focused on physical disability – that’s why it’s ESSENTIAL to get help from someone who knows the system to complete them.

Overall, be ready for a long journey. It’s taken you some time to find yourself with BPD it will take some time to find your way back. Some people get better from this – but be prepared for not being ‘Cured’. The best that many (myself included) can hope for (and believe me, this is a fabulous outcome) is the management of their condition.

I lose roughly a third of my life to dissociation (one of my BPD symptoms). I no longer fight it. I no longer judge myself for having it. I no longer fear it coming – that way I can live as much of my life to the full as much as I can. It took some time for me to get to that point too.

PDAN: Why do you think it is important to tackle stigma?

Chris Young: A friend once told me that ‘Stigma’ is an overused and not well-defined phenomenon. We don’t all agree on what it is. Roughly, I believe that Stigma is a negative belief system held about an individual or group of folk. Discrimination is when we act on these flawed beliefs. We are hardwired to see difference and to prejudge (as in prejudice); it’s what we do with these prejudices that matters.

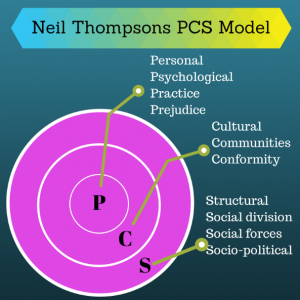

Neil Thompson came up with a theory that discrimination works on 3 levels:

- P(ersonal) where someone discriminates against you/ your group as an individual. For example, when I told my psychiatrist I intended to meet with a peer support group of folk with BPD and she declared, ‘No, you mustn’t – these are very sick people!’

C(ultural) where a discrete group of people holds a stigmatising belief against an individual or group. For example, when I worked as a nursing assistant in a psychiatric hospital, the staff on the Ward held an ‘us’ and ‘them’ attitude against the patients – for example, a woman with BPD was constantly deemed to be ‘manipulative’ and ‘attention seeking’ – a set of beliefs that are utterly self-fulfilling. Try this on anyone you know – in no time at all it becomes easy to label anything/ everything they do as either manipulative or attention seeking – often both.- S(tructural) stigma is where a body representing society acts in a way that discriminates against an individual or group.

For example – our welfare benefits system discriminates against people with mental health problems. The application forms for benefits make it more difficult for people with mental health problems to claim the benefits to which they’re entitled. People with mental health problems are over represented in the benefits sanctioning system (where folk can have their benefits stopped for between 3 days and 3 years) for missing a meeting or filling out a form incorrectly.

If we only challenge stigma/ discrimination at one of these levels (usually the personal) then nothing will change!

PDAN: What positives do you find in your diagnosis?

Chris Young: It validated my feelings of mental ill health – it helped me to know that people who’d had similar life experiences to me where experiencing similar symptoms to me. Without the diagnosis I wouldn’t have met up with the folk from the peer support group. Without the diagnosis I’d still be struggling with ‘What’s wrong with me?’

PDAN: What do you think of the support available from the NHS?

Chris Young: The cuts in the NHS mean that the therapies offered are often mismatched to the needs of people with BPD. The stress that many mental health workers are under can lead to the bizarre situation where

individuals with BPD aren’t improving, when it’s down to shortcomings in the services.

It’s a postcode lottery for so many people with BPD!

More ringfenced money is required now. Without that, nothing will change. In recent times we’ve been told £billions had been set aside for mental health services – only to later find that it had been used as a general contingency fund to pay off other NHS debts. Any money in the future must be ringfenced.

PDAN: Not having a job is something a lot of our followers struggle with. How did you cope with losing your job?

Chris Young: It was devastating. Social work was the job I’d wanted to do since I was 12 – because no one had been there for me – I’d wanted to be there for others. I left the family home – presenting myself as homeless at Edinburgh’s housing department.

I was gutted that I was no longer able to provide for my children. Because I was a social worker, I knew the system: Housing/ services/ benefits. Even then it was made very difficult. I dread to think what it must be like for people who were unfamiliar with it.

Society defines us through what work we do. When we meet someone new at a party, that’s one of the first questions, ‘So, what do you do?’

We’re told that, as a society, we’re dealing with issues surrounding mental ill health better. Regarding the world of employment, I think we’ve still got a long way to go.

For example – last year around 300 thousand folk in the U.K. lost their jobs due to mental ill health. Although there’s legislation in place that states that employers must make reasonable adjustments for people with disabilities in the workplace, we still don’t know what a mental health ramp looks like.

Because I lose roughly a third of my life to dissociation, persuading an employer to employ me in those circumstances is a challenge. Most employers in the U.K. are chronocentric – keen for their employees to turn up between 9 & 5 – and are less concerned with what folk actually do.

Over the past few years, I started the walk a mile campaign. I headed up the huge LetsWalkAMile campaign with #SeeMe – including the development of a brand – working with mainstream and social media.

I was the subject of a film which was well received at the Scottish Mental Health Arts and Film Festival. Although this work was very intensive at times, I was only ever paid expenses.

One of the reasons for setting up the charity was to demonstrate how to employ folk with mental health problems in a meaningful way. It feels like we’ve still got some way to go. I’ve written a book! Hopefully this will help things change for me. But for others with mental health problems? I’m not so sure.

PDAN: What would you say to people who do not want to keep on living due to BPD? What gives you the strength to keep fighting?

Chris Young: This is a very personal thing – I’m sure different folk have different reasons for wanting to take their own lives. For me, psychotherapy helped me work out what my suicidal ideation was about. First and foremost – for me – I don’t want to die – I just want the racket in my head to stop.

I’ve a friend who has a phobia about hospitals – but he wanted to be present at the birth of his first child. The consultant took him to the maternity suite – and guided him through the 4 doors to the way out. Knowing there is a way out helped my friend to deal with the stress of the hospital.

And that’s what I feel suicidal ideation is – it’s the minds way of alleviating stress by showing there’s a way out. It’s a way out I don’t have to take – but it helps knowing it’s there. Again, I can only speak about me here. My suicidal thoughts only rear up at times of stress/ times when I feel mentally bad – they’re not always there. With my dissociation and suicidal thoughts, I’ve learned to use a simple mantra, ‘This will pass’ and it always does.

Even with all the pain and mental shenanigans, I live a full life. I live differently from others – I think of it as making hay while the sun shines.

PDAN: If you were given 3 wishes, would 1 of them be to not have BPD?

Chris Young: Ground zero for my BPD was when my mum died. We need to move away from the ‘What’s wrong with you?’ rhetoric to ‘What happened to you?’ I wish mum hadn’t died until I was at least into adulthood – that way she would have continued to manage Dad’s alcohol problem and I wouldn’t have asked for help from the person who sexually abused me. I believe without that chain of events I wouldn’t have BPD – I’m sure I’d still be a bit flowery around the edges – but I firmly believe that events sit at the corner of all cases of BPD.

PDAN: Why walking and talking?

Chris Young: When I was a social worker, I found that the across the desk interview was less effective in getting a meaningful conversation with folk than in circumstances where we’d use a ‘third object’.

The best example of this for me was before I became a social worker, when I was a was a nursing assistant in a psychiatric hospital. There was a patient on the Ward who was making a name for himself as the ‘Karate Kid’. He had a habit of breaking the bones of male members of staff with a strategically placed kick. It got to the point where I was the only male member of staff who hadn’t been karate’d. He developed the habit of appearing behind me, saying, ‘Here I am, Chris,’ in a quiet, sinister manner. I decided I wasn’t willing to wait to be kicked in the head. I told him he was scaring me – I told him that if he continued battering folk, it would, er, delay any discharge plans he might have.

I asked him about himself – what his interests were. It turned out he’d been on the cusp of becoming a professional footballer. I enjoyed playing football, so it seemed a natural progression for he and I to use the recreation area for regular kick abouts. We used our time together to talk about his hopes and dreams – it was easier for him to talk when we had a third object – playing football – to take the intensity away from the conversations we had. He didn’t hit anyone for the rest of the time he was on the Ward. We found that his violence on the Ward was really a case of him exerting power in an environment where he felt powerless. He returned to live in the community with support.

Walking provides a third object for many folk.

Regarding the walk. I felt that many of the larger charities were failing to engage the wider population with their anti-stigma campaigns. They’d invite the same old folk to their events – people who already had positive attitudes towards people with mental health problems.

With the coastal walk I speak to anyone and everyone – most of whom are completely unaccustomed to talking about mental health. I think, since it’s taken us years to get to this point of mistrust of people with mental health problems, it’s going to take some time to change that way of thinking. That’s where the tagline ‘Challenging mental health stigma, one conversation at a time’ came from.

PDAN: Our followers come from all over the world. How can they get involved?

Chris Young: Keep the conversation going. Join up to the Walk a Mile Facebook group/ page. Read books that challenge the rhetoric around mental health. Gently challenge those around them who believe the negative splurge from much of the media. This will be a slow process – but I really believe we’ll get there.

PDAN: We were so happy to read that you have found your old English teacher, how do you feel about this?

Chris Young: I’m deliriously happy. I’m so keen for her to know the positive impact she had when my world was …er… dark.

I’m seeing her on Friday!

A note from PDAN.

Firstly, thank you Chris for sharing your experiences with us!

We hope you’ve enjoyed reading about Chris’ experience and feel relatively inspired! If you want to get involved or learn more about ‘walkamile’ follow this link: LetsWalkAMile.org.

Please share your thoughts and views on this in the comments section below.

As we’ve previously stated, we encourage creating a conversation on the topics spoken about throughout this interview. Please be respectful of other people’s viewpoints.

– Jessica Ramplin and Leila Solomons

PDAN Admin Volunteers

I have a family member diagnosed with anxiety disorder. I want to learn how to help.

Hi Chris,

Enlightening story.

Were you ever a social worker in Canada?