What’s a trauma-informed school? It’s a place where this happens:

There’s this third-grade kid. Let’s call him Sam. He’s got ODD (oppositional defiant disorder…a misnomer for normal behavior a child exhibits when he’s living with chronic trauma).

Nine-year-old Sam (not his real name) is very smart. But sometimes he balked, dug his heels in deep, refused to work in class. So his teacher sent him to see the principal. Often.

The teacher and the principal knew something about his home life. At night, Sam sleeps on a couch. Dad sleeps on the other couch. The TV’s on all day, all night. When Dad’s awake, he always has a computer in his lap. Mom drifts in and out of the home. His parents have little to do with their son. They rarely touch him.

“He obviously needed hugs, and I was giving him those,” says the principal. But it wasn’t quite getting Sam out of his funk or making enough of a dent in his class behavior. “One day, I was teasing him and as he moved away, I poked him a little,” she recalls. “He laughed, and his eyes lit up. I did it again, and he laughed, and loved it.” In fact, he howled with laughter, inviting more tickles.

Not only was Sam not getting hugs at home, the principal realized, but his parents weren’t playing with him, either.

So, now Sam knows what he needs and where to get it. Three to five days a week, he walks into the principal’s office to be tickled and hugged.

“If people looked in and didn’t know what was going on, they would say I’m torturing this kid,” says the principal, because Sam rolls on the floor and shrieks with laughter. “It’s not usually what I do with kids. But he needs touch. So, I tickle him for a while. Then he falls into my lap, gets some hugs. Then he straightens up and says: ‘I’m ready to go to class.’ ”

Sam’s calmer and happier. And, because he has a caring adult who’s giving him the basic human interaction that’s necessary for him to grow into a healthy adult, his brain, which gets big doses of blinding toxic stress at home, returns to a more open, peaceful state so that he can focus in class.

______________________

By now, some of you are muttering: “Schools shouldn’t have to deal with kids’ problems – their parents need to take responsibility.” “The parents are to blame.” “The parents need to pull it together.”

There are two schools of thought here (pardon the pun).

School of Thought No. 1. You can point the finger at parents and wait for them to change. Counseling would help, but they’d have to agree to participate. Free or low-cost counseling for people who can’t afford it isn’t a given in these days of social service budgets stripped to the bone. And, counseling would take months, if not years to change the family dynamics. In the meantime, the boy continues to suffer and his behavior grows more belligerent.

School of Thought No. 2. Change the schools to become safe and nurturing, so that kids can learn no matter what’s going on at home…or in their neighborhoods…or in their extended families. The reality is, a school’s traditional response – suspending, expelling or putting a child like Sam into special education classes – further traumatizes already traumatized children. That’s the tried and true road to prison or dropping out of school, and a life damaged for no good reason.

In 2008, the Spokane educational community decided to embark on approach No. 2.

Abandoning the punitive, one-size-fits-all approach to school discipline takes courage. Teachers, principals and school staff must jettison generations of tradition and belief that severe punishment works to stop bad behavior. They have to stop believing in the concept of bad kids, and to start believing that all kids are good, but that many of them have troubles over which they have little control. They have to believe that they — the teachers, not therapists — can be the first line of defense for kids who are living really tough lives. And they must create an environment where kids feel safe enough to blossom into the natural learning machines that they are.

Seven years later, about 275 education pioneers at six elementary schools in Spokane are proud to say that they’ve become trauma-informed. They also say they’re never going back to the old ways.

If you want change that sticks, be a turtle…not a hare

Chris Blodgett has been working on issues of family violence most of his career. About 10 years ago, he ran across research that shows how toxic stress is at the root of family violence (more about that shortly). He got it in his head that the best way to help children and families was to change universal systems “to bend the curve on the risk and consequences of exposure to trauma.”

One of those universal systems – one that touches every single person in a community – is education. That curve – now steadily tracking toward the Moon — represents an epidemic that’s so widespread it looks like normal life (more on that in a bit, too).

Blodgett is about as low-key and down-to-earth as they come. A psychologist and researcher, he looks at solving social problems through a systems lens. He’s one of those people that most others underestimate. So when he says, “Let’s change the entire educational system,” people don’t take offense. In fact, they listen and are willing to try approaches that, if suggested by anyone else, they’d flat-out say nope can’t work no way not possible uh-uh never happen.

As director of the Washington State University Area Health Education Center (AHEC), Blodgett leads an organization that is as understated as he is. In less than six years, they’ve gone from holding a few workshops for the community of Spokane, to attracting interest and support from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the U.S. Department of Justice, and the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA — the largest federal agency you never heard of) to help schools throughout Washington become trauma-informed.

“I run a research and development unit,” says Blodgett, who’s also overseeing research into the effects of childhood adversity in Head Start programs. “We took this on as a self-funded effort. Our first efforts took the form of a classic public awareness campaign.”

He was convinced that if Spokane’s teachers knew:

- that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are an epidemic that’s growing;

- that these ACEs contribute to a huge amount of the burden of chronic disease in this country, as well as most mental illness and violence;

- that they interfere with children’s ability to learn in school;

- and that the educational system can help reverse the trend….

…..that they’d be chomping at the bit to do something about it. Here’s why:

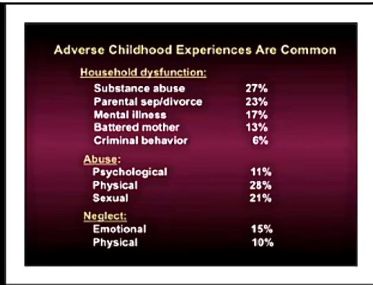

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) groundbreaking epidemiological research, the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study – the largest, and arguably the most profound, public health study you never heard of — measured 10 types of childhood trauma in 17,000 people. Five types were the usual suspects: physical, sexual and verbal abuse; physical and emotional neglect. Five were family dysfunction: a parent who’s addicted to alcohol or other drugs, is diagnosed mentally ill, a mother who’s a victim of domestic abuse, a family member in prison, and loss of a parent due to divorce or abandonment.

In a nutshell (you can read a story about the ACE Study here), researchers Robert Anda and Vincent Felitti found:

- A direct link between childhood trauma and the adult onset of chronic disease (including cancer, heart disease and diabetes), mental illness, violence, being a victim of violence, divorce, broken bones, obesity, teen and unwanted pregnancies, and work absences.

- That ACEs are as common as salt. About two-thirds of those in the study experienced one or more types of severe adverse experiences during childhood. (Physical abuse, for example, is being pushed, grabbed, slapped, or had something thrown at you often or very often, or ever being hit so hard that you had marks or were injured.) Of those, 87 percent had experienced 2 or more types. And these were 17,000 middle-class, college-educated, mostly white, employed people with great health care (they all belonged to Kaiser Permanente HMO in San Diego).

- The more ACEs a person has, the higher the risk of medical, mental and social problems as an adult (Got Your ACE Score?). Compared with people who have none, people with four types of ACEs are twice as likely to be smokers, 12 times more likely to attempt suicide, seven times more likely to be alcoholic, and 10 times more likely to inject street drugs.

The CDC’s ACE Study found that childhood trauma was very common.

The CDC’s ACE Study found that childhood trauma was very common.

____________________________

Brain research revealed one of the reasons: the toxic stress of this trauma damages the structure and function of a child’s brain. Kids become anxious and can’t sit still; or become depressed and withdraw; or become angry and fight. They can lose focus and stop learning. As they get older, they cope with anxiety, depression, and anger by drinking, smoking, doing other drugs, fighting, stealing, overeating, having inappropriate sex, participating in thrill sports, shedding marriages like a snake sheds skin, and/or becoming overachievers on their way to becoming workaholics.

Twenty-one states have done or are doing ACE surveys, as have pediatricians, social services organizations, cities and towns. In similar populations, all have found similar results to the CDC’s ACE Study. In high-risk groups — teens or young adults who areclients of services for troubled youth or who attend an alternative high school, for example — childhood adversity is heartbreakingly high.

It took just a few workshops and presentations to set the community abuzz about ACEs. Blodgett was astounded.

“I’ve been working on child maltreatment for 25 years, and I’ve never ever had a set of concepts catch fire with people in the community the way these ideas of ACEs and trauma have,” he says.

In 2008, 700 people showed up for From Hurt to Hope, a two-day conference that AHEC co-sponsored with the Spokane County Community, to hear ACE Study co-founder Dr. Robert Anda and education expert Susan Cole, author of Helping Traumatized Children Learn (AKA “The Purple Book”). After Anda explained why childhood adversity is the nation’s largest public health crisis, and Cole told the audience about the trauma-informed school movement in Massachusetts, Spokane educators wanted to hear more.

For the next two years, Blodgett and his staff visited dozens of schools. “We had to be invited in,” says Natalie Turner, AHEC’s assistant director. “This couldn’t be imposed as a structure on schools. When you’re explaining the neurobiological effects of traumas on kids, you can’t expect people to change overnight. This is a two- to four-year change process. You have to say it multiple times.”

That’s because our whole culture is solidly stuck in the shame-blame-punishment model of responding to children’s (and adult’s) behavior. Letting go of the mindset that kids behave badly because they’re out to “get” teachers, or they’re being “intentional” or “willfully defiant”, or that their parents are all “bad” and “should know better” takes a while, even in the face of overwhelming research from several different scientific fields, including epidemiology, neurobiology, biomedicine, and epigenetics.

At each school, the AHEC staff did a one-day workshop in which teachers, principals and school staff learned about the ACE Study, brain development, the effects of toxic stress on how children bond with their parents, how critical that attachment is to children’s health, and the fallout when attachment doesn’t occur. They learned about how toxic stress affects children’s ability to regulate their emotions and behavior, and how it interferes with children’s ability to learn.

“We were making the case for why educators need to pay attention,” says Blodgett. “We were trying to make the case for why it was important.”

The awareness efforts began to take hold. “We could see that educators were starting to think about their school environment differently,” says Turner. They began to look at the fear-based, punitive, deficit-driven system with new eyes, and it didn’t look good. It looked as if their system was actually hurting kids, not helping them.

In 2010, 900 people showed up for a two-day conference, From Hope to Resilience. This time, they focused on solutions – how to integrate resilience factors into a school, in teachers and in students. (This conference lit a fire under Jim Sporleder, principal of Lincoln High School in Walla Walla, WA, where suspensions dropped 85% the first year he instituted trauma-informed practices.)

Later that year, Blodgett and his staff published the results of a study of 2,100 students in 10 Spokane elementary schools. The news hit Spokane in the gut, and made all this talk of ACEs and trauma and the effects of toxic stress extremely personal.

The study found that ACES were:

- as common in Spokane’s children as ants at a picnic,

- the main reason that children missed school or got into trouble,

- the second-highest predictor of academic failure, after a child being in special education classes.

The more ACEs a kid had, the study showed, the more likely that child was to have failing grades, poor attendance, severe behavior problems and poor health.

“The 248 kids with three or more adverse childhood experiences had three times the rate of academic failure, five times the rate of severe attendance problems, six times the rate of school behavior problems, and four times the rate of poor health compared with children with no known trauma,” says Blodgett.

This research attracted the interest of the Gates Foundation, which gave AHEC a 2.5-year $250,000 grant to develop a pilot project in six of Spokane’s elementary schools, to “shift the building culture and practice to make it sustainable,” says Turner.

Fast forward to the spring of 2013. The culture in those six schools has flipped 180 degrees, from a one-size-fits-all punitive approach to school discipline, to an individualized, compassionate approach to discipline and learning.

The hidden iceberg and the dinosaur brain

About 35 teachers crowd around five low tables in the library at Bemiss Elementary School. Across each table lies a huge laminated image of an iceberg. It’s that image that’s zipped around the Internet about a million times – it shows the tiny top above the waves and the HUGE part underneath.

Bemiss Elementary School teachers work on case study in workshop, part of their training in becoming a trauma-informed school.

_______________________

Turner is taking one hour of these teachers’ time, as she has done once a month during the last two school years on this slow, steady passage to becoming trauma-informed. At the beginning of each school year, Turner and two other AHEC colleagues did a one-day kick-off training. Each week, one spends a half-day at the school to help teachers, advise on challenging situations, and work with the public health nurses. They’ve done the same at each of the other five elementary schools.

Nearing the end of their two-year training, the teachers are perfecting their craft, refining their actions, smoothing out a few rough patches.

Natalie Turner, assistant director of the Washington State University Area Health Educations Center, leads a workshop for Bemiss Elementary School teachers.

_________________________

Each group uses the iceberg to tell the story of a child they all know. (A group comprises all the teachers from the same grade.) The point of this exercise is to help teachers recognize all the steps – the underwater parts of the iceberg – leading up to a child’s explosion or withdrawal – the flight, fight or freeze response to toxic stress. That’s the jagged top of the iceberg that everyone around that child, including other children, can’t help but witness and are often upset by. And then to examine the steps that calm a kid down. If they intervene early, the kid will never break the surface of the water to land on that iceberg’s peak.

“I can see it on his face,” says one teacher describing what happens when one of her students gets triggered. “He starts to tear up. His eyes move around. He won’t focus on me or the task. He’s frozen except for his eyes. There’s something going on in his head.”

She’s putting her knowledge of the effects of toxic stress on children’s brains to work. A kid who lives with a raging parent — one who screams more often than speaking in normal tones — can be instantly triggered by a teacher’s raised voice, even if she raises it just to be heard. This teacher knows that when the student freezes and starts tearing up, his brain is careening into basic survival mode. He’s scared. The only action he’ll take is one his dinosaur brain will make for him: to run, freeze or fight. He certainly isn’t able to learn. Any further push will send him further out of control. But intervening right away – such as having him to sit next to her while he works — will bring him back.

Jennifer Keck, principal of Bemiss Elementary School, works on a case study with teachers during a workshop on trauma-informed practices.

______________________

“I can tell when he comes out of it,” she says. “He’ll respond to me. He’s more relaxed. A lot of times, he apologizes.”

The teachers also discuss how to control their own emotions, because what they show their students can escalate a situation.

“I have to be aware of that,” says another teacher, “because he’ll say, ‘Are you mad at me?’ “

Besides brain science and the ACE Study, Turner uses the ARC model developed by Dr. Margaret Blaustein and Kristine Kinniburgh, staff clinicians at the Trauma Center at Justice Resource Institute in Brookline, MA. “We give school staff real practical tools they can use to manage their emotional response, create consistency in their classrooms through routines and rituals, and to give skills to kids to control their own behavior and emotions,” explains Turner. (ARC stands for attachment, regulation and competency. For more information, read a description of the model written by Blaustein and Kinniburgh.)

“We’re not trying to lower the bar for kids with trauma,” Turner continues, “but we have to make sure that we’re giving them tools so that they can learn. We have to make sure they have adults they can count on, who aren’t going to hurt them, who’ll be there to support their process, who will meet them where they’re at and build from there.”

“Safety” takes on a whole new meaning in a trauma-informed school. “If children are homeless, if mom or dad is in jail or getting out of jail, they can’t concentrate,” says Turner. “How we can create environments so that they feel safe enough to focus on instruction? Safety takes on a very different definition.”

Most people think a safe school is one that protects children from gun-toting intruders, a remarkably rare occurrence in U.S. schools. As important, a school should feel safe for the millions of kids who live in very unsafe environments – homes in which they’re brutalized or they witness violence or where they’re neglected; or in neighborhoods that do the same.

Both Turner and Blodgett point out that they have no intention of turning teachers into therapists. They’re equipping them with good knowledge and, in their role as educators, to respond appropriately to students. “We’re not putting more on their plate,” says Turner. “This is their plate.”

In today’s exercise in the school library, Turner also reinforces that each child is different, so the response to each child must be different. There’s no cookie-cutter solution. If teachers know how trauma affects each child, if they know how to build resilience in each child, and how to create safe classrooms, then kids will have fewer explosions, fewer times when they tune out because they’re scared.

“If there’s chaos,” says Turner, “kids don’t feel safe.”

As one group goes through the exercise, a teacher comments: “This year, there aren’t as many blowout kids. I don’t know if it’s the kids, or if it’s us.”

Turner knows. It’s the teachers.

School discipline, no. School expectations, yes.

Many schools in the U.S. are moving from a punitive to a compassionate approach to school discipline because the research is irrefutable: Suspensions and expulsions don’t work. They’re just ugly symptoms of school systems lurching down the zero-tolerance road to nowhere, of adults clinging to a broken educational system that emphasizes test results above making sure every child has the opportunity to learn, and of racism embedded deep into our systems like the roots of a 200-year-old tree.

Because Spokane decided to make a commitment to trauma-informed education, the transition hasn’t been easy or quick. “We’re not coming in to wave our magic wand,” says Turner. “We knew going into it was going to be hard work, it was going to be a slow change process. Here we are five years later, and they continue to carry forward with less and less handholding from us. That’s evidence it’s working.”

Unlike other frameworks or programs, the AHEC staff never presented themselves as coming in and “giving us the magic bullet,” says Bemiss school counselor Melissa Kopcynski. “This is about us finding the answers for ourselves as we make the journey. It’s about them keeping us on the journey, providing us with insights, being the outside person who can help us process, giving us a fresh look on what we’ve done, keeping us motivated, and keeping it in the forefront, because it’s easy to get bogged down with daily tasks and needs.”

The educators I talked with noted three important aspects to integrating trauma-informed practices into a school.

1. The practices “filled in a missing piece on how to approach kids,” says Lori Johnson, principal of Broadway Elementary School. The traditional response when a child is not doing what a teacher wants her to do, says Johnson, “is to take it personally, to see it as defiance, to see it as a threat to what we’re trying to do.”

Lori Johnson, principal of Broadway Elementary School.

______________________

The training provided a useful foundation from which to work with children. “I always believed that kids don’t do their best thinking when they’re in their dinosaur brain. I always tried to get them calm, but I never had a framework to put it into.”

Before the training, educators used to look more at students’ deficits,” says Jennifer Keck, Bemiss’ principal, “instead of looking at the little steps it takes to help them get better.”

One place she noticed a change was in the teachers’ lunchroom, says Whitman Principal Beverly Lund. Teachers who used to gripe about how a student was “acting like a little princess” now start a discussion on how to help a child move to a place where she or he is open to learning.

Beverly Lund, principal of Whitman Elementary School talks with Natalie Turner (back to camera).

______________________

2. They caused a shift in staff. Teachers who did not buy in to the changes transferred to other schools. And now, new teachers are screened for their approach to discipline, their commitment to becoming trauma-informed, and their ability to collaborate — to be a member of a team to work together on how to best help each child.

3. Trauma-informed practices are the foundation for, but are not meant to replace other frameworks such as PBIS (Positive Behavioral Intervention and Support), Safe & Civil Schools, CBITS (Cognitive Behavioral Intervention for Trauma in Schools), or restorative justice, says Blodgett. Becoming trauma-informed not only supports those approaches, it’s the bedrock for all of them. “We believe a grounding in ACEs and the effects of toxic stress on the neurobiology of children’s developing brains are the fundamental set of mechanisms” that result in sustainable change, he says.

PBIS provides a systematic approach to develop a school-wide set of behavioral expectations for all children, says Johnson. “A lot of kids don’t know how to walk in a line or solve problems with each other. PBIS provides a mechanism for rewarding positive behavior.”

“Kids are not blowing out in the way they were before.” she continues. “We’ve changed the philosophy, from negative to appropriate consequences. It’s not about me creating fear in in a student so the kid behaves; it’s about helping a student.”

Says Jennifer Keck, principal of Bemiss Elementary: “We don’t call our system school wide discipline anymore. We call it school wide expectations.”

What’s a public health nurse got to do with this?

When local health budgets were eviscerated, the Spokane Regional Health District risked losing the deep connections with the community that public health nurses had developed in their work with young mothers and infants. So the health department worked out an arrangement with the school district to assign some of these nurses to schools.

If you look at life through a trauma-informed lens, this partnership looks like a positively brilliant move. The schools that have public health nurses are turning into community hubs where many families can access information, resources and support. And the nurses are beginning to work with the most troubled families to lower their ACE scores.

That’s because those children who live in dysfunctional homes have parents or caregivers who themselves were traumatized as children. They’re passing on the dysfunctional parenting they experienced to their children, as well as their dysfunctional coping skills. But it’s incorrect to assume that very poor or highly dysfunctional parents don’t care about their children, says Jennifer Keck. “That’s just not true.”

“The point is to not blame the kids,” says Melissa Charbonneau, a public health nurse who works closely with 30 families of students at Whitman Elementary. “And to not blame the parents. They grew up with these traumas, too. They are still traumatized. They’re trying to cope. Doing this drug helps me cope. Using alcohol gets me through the day. They steal to buy food for their families. They don’t know a different way of coping. It looks very dysfunctional, but this is what has worked for them.”

Melissa Charbonneau, public health nurse assigned to Whitman Elementary School, started screening families for ACEs this year.

________________________

What some of the families believe is normal “is out of our realm of understanding,” says Whitman Elementary Principal Beverly Lund, who says she’d just heard from a family who’s moving to Florida because the father has a job prospect.

“They’re getting on a Greyhound Bus,” says Lund. “They have $200 to their name. All of their belongings – the parents’ and the kids’ — fit into one large duffel bag.”

Charbonneau establishes a relationship with the families whose kids are having the most difficulties. First she figures out what families need, then helps parents sign up for medical care, food stamps, transport to and from doctor appointments. She helps them obtain mental health assessments, for them and their children. She helps them find housing, domestic violence intervention and respite care for elderly parents. Then she helps them move one small step at a time toward making healthier decisions for themselves and their children. It takes a long time to win the trust of these parents, who have often had miserable experiences with systems that are supposed to help them. Hence, says a remarkably patient Charbonneau, this process can take months or years.

This year, Charbonneau started screening families for ACEs. “If trauma’s going to be our focus, then we need to be able to address what their trauma history has been and how it’s impacted them,” she explains. “We have a conversation, explain to them: This is what’s happened to you, and this is how it affected you. None of what happened to you is your fault. You made coping decisions that were appropriate at the time. Now that you know this, how would you like to move forward? What do you need so that your child doesn’t have a high ACE score?”

The reaction of parents? They’re usually relieved, says Charbonneau. “One mom who has a history of meth addiction, her response was: ‘I can’t believe what I’ve done to my child.’ Some people get stuck there. We keep having the conversation: Yes, but that’s history. Now, it’s about choices you make. What would you like things to look like? What kinds of things do you want to put in place? This process is a validation of their history. It’s an acceptance of them. And then it’s about moving towards a different way of living.”

Happier, calmer kids = fewer blowouts, more learning, more awards

As you might expect, the schools that have been working on this the longest have seen the most profound changes; schools that are relatively new to the process are just seeing the first effects of the transformation.

Bemiss Elementary has seen a 30% drop in suspensions and a 20% drop in teacher’s referrals to the principal’s office each year for the last two school years. “We have been a trauma-sensitive school for the past seven years,” says Bemiss Elementary Principal Jennifer Keck, “so this work is continuous and runs deep. We have had very little staff turnover in the past two years due in part to our commitment and support of our work to conscientiously address student and family needs at home and at school through a trauma-sensitive lens.”

The incidents of aggressive behavior — pushing, hitting, physical aggression – at Otis Orchards Elementary dropped from 83 during January to April 2012, to 13 during the same period this year, says Principal Suzanne Savall. “And we’re in the top 5% of state schools in improvement of overall reading and math test scores.”

Suzanne Savall, principal of Otis Orchards Elementary.

________________________

Broadway Elementary came to the trauma-informed approach three years later than Bemiss. Principal Lori Johnson has been there only two years, and the turnover in teachers is still high. During the 2012-2013 school year, there were 529 referrals and 95 suspensions in a school of 465 students, 72% of which live close to or below poverty level. The school wasn’t keeping data before they implemented PBIS, so Johnson can only compare Broadway with a school with similar demographics that hasn’t implemented trauma-informed practices or PBIS – and that school’s suspension and expulsions are much higher.

Johnson notes that Broadway has become less chaotic and students are spending more time in class, which may have contributed to the school receiving the Washington Achievement Award this year, for being one of the top 5% of the schools in the state in science. It’s the first time the school has received the award.

The changes in these schools have not gone unnoticed. All other schools in the Spokane district are clamoring for training, and Blodgett is receiving requests from other parts of the state and from schools in other states.

To meet the demand, AHEC received a four-year grant from the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to be part of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. That’s allowing them to expand into 21 more schools in five regions across Washington this Fall, including five more in Spokane County. During the last three years of the grant, they’ll add about 10 schools a year. Most are elementary schools, but they’re adding middle, high, and alternative schools, and one all-kindergarten school. The Gates Foundation has also provided a grant for AHEC staff to work with two elementary schools in Seattle.

In Spokane, the next big step will come at the school district level, to look at policy and procedures around discipline and classroom management through a trauma-informed lens, says Turner. That will ensure that this approach is firmly embedded in the local education structure.

Meanwhile, Blodgett continues to keep “a research dimension to this work.” It’s part of reinforcing the notion that trauma-informed schools are critical for children and the communities they live in.

The latest study only adds more urgency. Blodgett looked at the ACE scores of 5,443 students from 91 school districts in Washington State. They were all part of the state’s Readiness to Learn program that targets students who are at risk for dropping out of school.

The study confirmed the findings in Spokane: ACEs are common, and they impair children’s school lives. Half the students had an ACE score of two or more; 25 percent had an ACE score of three or higher. Children with four or more ACEs were twice as likely to fail academically, three times more likely to have behavior problems in school, five times more likely to have attendance issues, and six times more likely to have behavioral health problems.

“The risk of ACE exposure is immediate, significant, and directly affects the success not only of individual children, but of educational systems,” Blodgett summarized.

To make school what it’s supposed to be – a safe place to learn – instead of a place that metes out sentences to a damaged life…in prison, on the streets or of dreams unfulfilled… the six elementary trauma-informed schools in Spokane are well on their way in their quest to reverse the epidemic of adverse childhood experiences.

At one of those schools, there’s a boy who doesn’t yet understand what adverse childhood experiences are, or their significance in his life. But Sam knows that if he stops off on his way to class at the principal’s office for a hearty dose of tickles and hugs, he feels better. And then he’s ready to do what kids do best when nothing gets in their way: learn.